For every PlayStation and Nintendo Switch that dominates the market, the video game industry’s boneyard is littered with the plastic carcasses of consoles that bombed spectacularly. These aren’t just commercial failures—they’re cautionary tales of hubris, terrible timing, and designs that left gamers scratching their heads instead of mashing buttons.

Some were technological marvels ahead of their time, others were cash grabs that insulted players’ intelligence, but all share one thing in common: they flopped harder than a soccer player trying to draw a penalty. From bizarre control schemes to battery-devouring portables and consoles with more ambition than common sense, these gaming disasters remind us that innovation without execution is just expensive garbage.

So power up your nostalgia and dust off your wallet—we’re diving into gaming history’s most fascinating failures, ranked from merely misguided to catastrophically misconceived. These systems might have crashed and burned, but their stories are anything but game over.

12. Epoch Cassette Vision

Japan’s first cartridge-based home game system bit the dust faster than you can say “power failure.” Released in 1981 for ¥13,500 ($61), the Cassette Vision briefly dominated Japan’s gaming scene before Nintendo’s Famicom staged a hostile takeover. The system’s bizarre design placed essential components inside the game cartridges rather than the console itself—a penny-pinching move that backfired spectacularly.

Why did this electronic paperweight fail? The console’s controls were literally bolted to the system—imagine being tethered to your TV like some kind of gaming prisoner! With a measly 4-bit architecture when competitors embraced 8-bit, a palette limited to just 8 colors, and resolution that made Atari look cutting-edge (75×60 pixels!), the Cassette Vision was fighting tomorrow’s war with yesterday’s weapons.

By 1985, Epoch waved the white flag after selling about 500,000 units, while Nintendo’s Famicom was crushing it with 2.5 million first-year sales alone. The lesson? Don’t bring a calculator to a computer fight.

11. Vectrex

The Vectrex (1982) was gaming’s equivalent of bringing a protractor to a gunfight. This oddball console came with its own built-in 9-inch vector monitor when everyone else was connecting to TVs. Cool concept, but the execution left gamers seeing green—literally.

Instead of colorful raster graphics that Atari and others were using, the Vectrex drew everything with glowing vector lines powered by its Motorola 68A09 processor running at a blistering 1.5 MHz. The kicker? It only displayed things in black and white! The “solution” was a stack of colored plastic overlays you’d slap onto the screen. Imagine trying to add color to your flat-screen TV with cellophane—that’s basically what Vectrex asked you to do with a straight face.

Each game came with its own custom-colored sheet of plastic that you’d clip to the screen, adding a static color layer that didn’t actually change with the gameplay. This wasn’t just a quirky feature—it was marketed as a revolutionary display technology! For the bargain price of $199 ($540 today), you too could experience the joy of manually changing screen colors like it’s 1942.

The timing couldn’t have been worse, launching just months before the great video game crash of 1983. Despite its innovative vector scaling that predated the SNES’s Mode 7 by nearly a decade, the Vectrex was buried alongside countless other gaming casualties.

10. Sega Genesis CDX/ Sega Multi-Mega

In 1994, Sega had a “brilliant” idea: “Let’s combine a Genesis, Sega CD, and portable CD player into one console that nobody asked for!” Enter the Genesis CDX (Multi-Mega outside the US)—the gaming equivalent of a Swiss Army knife where every tool is slightly broken.

This compact Frankenstein’s monster actually packed impressive tech: dual Motorola 68000 processors (one at 7.6 MHz for Genesis games, another at 12.5 MHz for CD tasks), 64KB of RAM plus 6.5 MBit of Sega CD memory, and a genuinely portable form factor at 5.5″×5.9″×1.6″. You could even run it on six AA batteries, which would give you a whopping three hours of playtime if you were lucky!

Sega priced this hybrid beauty at $399 (about $800 today)—more than double the cost of buying a Genesis and Sega CD separately. Talk about a value proposition! And the timing? Chef’s kiss. They released it just as they were pivoting to the Saturn, effectively orphaning their own product.

Sega themselves admitted the CDX was “more of a novelty item rather than a console designed for the mainstream audience.” Translation: “We made this thing but have no idea who it’s for.” With compatibility issues (it struggled with games like Jurassic Park CD and couldn’t properly connect to the 32X), the CDX sold fewer than 150,000 units before Sega pulled the plug faster than you can say “blast processing.”

9. Magnavox Odyssey 200

Yes, that Magnavox—the TV brand your grandparents swore by—once dabbled in video games. Their 1975 Odyssey 200 was essentially Pong with delusions of grandeur, running on Texas Instruments chips when most electronics still used vacuum tubes.

The Odyssey 200 offered three mind-blowing games: Tennis, Hockey, and the revolutionary “Smash” (spoiler alert: it’s just Pong with a different name). But the real innovation? The scoring system—or lack thereof. The console was so primitive it couldn’t even keep track of your score! Instead, you had to manually slide plastic markers below the screen when points were scored.

For the privilege of moving white rectangles around your TV screen and keeping score like it’s badminton in your backyard, Magnavox charged a mere $129.95 (roughly $640 today). Meanwhile, Atari was releasing actual digital scoring in their home Pong consoles, making Odyssey look about as cutting-edge as an abacus at a calculator convention.

With 30+ Pong clones flooding the market by 1976 and Atari selling 150,000 units monthly, Magnavox’s plastic wonder child was doomed faster than you can say “game over.” The company abandoned the entire Odyssey line in 1975 after selling about 500,000 units total—proving that sometimes, a TV maker should stick to making TVs.

8. Panasonic Q

In 2001, Panasonic looked at the Nintendo GameCube and thought, “This needs more stainless steel and a DVD player.” The resulting Panasonic Q was the gaming equivalent of putting a Rolex band on a Swatch watch—unnecessarily fancy and priced to ensure nobody would buy it.

This Japan-exclusive beauty packed identical gaming hardware to the standard GameCube (485 MHz PowerPC CPU, 162 MHz GPU) but wrapped it in a mirrorlike stainless steel chassis with a backlit LCD display. For audiophiles, it added optical audio with Dolby Digital/DTS support and a fancy remote control—features missing from Nintendo’s purple lunchbox.

Priced between ¥39,800 and ¥41,000 ($315-$500) when a regular GameCube cost just $199, the Q targeted Japanese consumers who wanted a premium DVD player that could also play Mario. Unfortunately, as standalone DVD players plummeted in price, the value proposition evaporated faster than a puddle in the desert.

Only about 100,000 units were manufactured before Panasonic pulled the plug in 2003, making this shiny oddity the Holy Grail for collectors today. Unopened Q systems now fetch upwards of $7,500, proving that sometimes the biggest failures make the best collectibles. Nintendo learned its lesson though—they didn’t add DVD playback until the Wii in 2006, and even then it was grudgingly implemented.

7. Sega Nomad

In 1995, Sega looked at the Game Boy’s massive success and thought, “Let’s make a portable that eats batteries like Pac-Man eats dots!” Enter the Nomad—a handheld that played full-size Genesis cartridges but required a backpack to carry the spare batteries.

The Nomad was technically impressive, featuring a 3.25-inch color screen and full compatibility with the Genesis’s 700+ game library. But Sega’s engineers apparently forgot that portable consoles need, you know, battery life. The Nomad burned through six AA batteries in about 2-3 hours—about as energy-efficient as carrying a small nuclear reactor in your pocket.

Sega’s catastrophic timing sealed the Nomad’s fate. Released just as they were abandoning the Genesis for the Saturn, the Nomad received virtually zero marketing. At $180 (about $340 today), it was competing with the Game Boy at $50 and the Game Gear at $100—both with substantially better battery life.

With the console market shifting to 32-bit systems and Sega spreading themselves thinner than a single-ply tissue, the Nomad became yet another footnote in Sega’s “How to Sabotage Your Own Success” playbook. No wonder they eventually threw in the towel on hardware altogether—their battery budget alone must have been astronomical.

6. Gizmondo

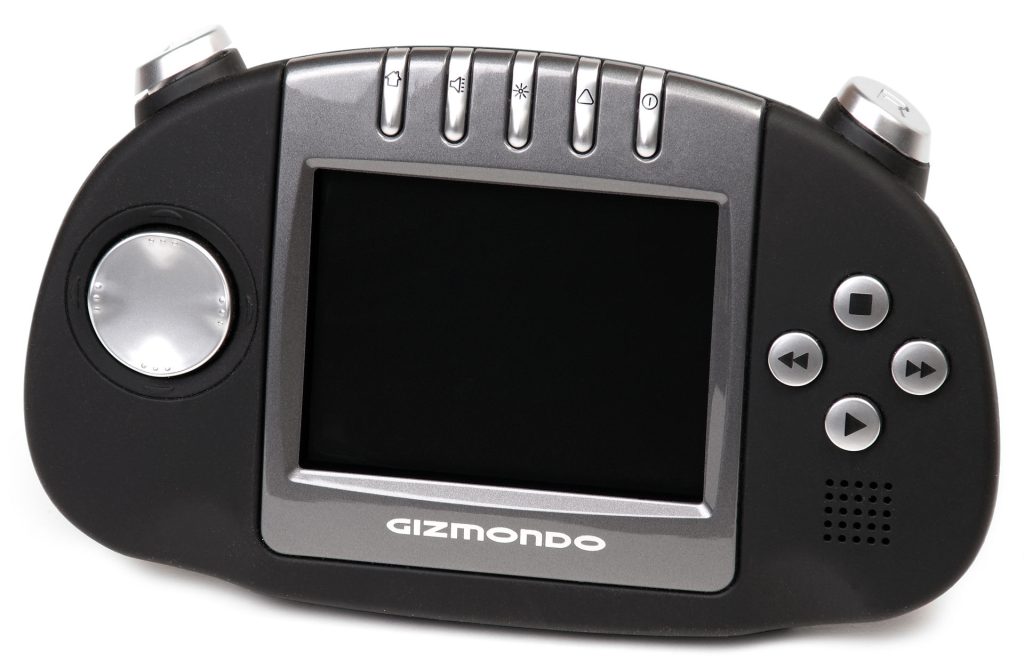

The Gizmondo wasn’t just a failed handheld; it was a spectacular train wreck that became a case study in corporate catastrophe. Released in 2005 by Tiger Telematics (not Tiger Electronics), this ambitious portable packed a 400MHz ARM9 processor, 2.8-inch screen, GPS, Bluetooth, and camera—essentially trying to be a smartphone before the iPhone existed.

What doomed this ahead-of-its-time device? For starters, it was connected to the Swedish Mafia. No, seriously—company executive Stefan Eriksson was later revealed to be “Fat Steven,” a Swedish Mafia member who crashed a rare Ferrari Enzo at 162 mph while claiming to be a German racing driver named “Dietrich.” You can’t make this stuff up.

The Gizmondo’s business model was equally bizarre, offering a cheaper model ($229) that forced you to watch ads or a premium version ($400) without ads. With only 14 games ever released and virtually no marketing beyond a gaudy store in London’s expensive Regent Street, the Gizmondo sold a pathetic 25,000 units before Tiger Telematics imploded with $300 million in debt.

The cherry on top of this disaster sundae? It took less than a year from launch to bankruptcy, making the Gizmondo possibly the fastest-failing console in gaming history. When your executive team is better at crashing supercars than launching tech products, perhaps gaming hardware isn’t your calling.

5. Apple Pippin

In 1996, long before the iPhone made Apple a trillion-dollar company, they dipped their toes into gaming with the Pippin—and promptly got those toes bitten off. Designed as a multimedia appliance rather than a dedicated console, the Pippin was Apple’s attempt to bring Mac OS to your living room.

Powered by a 66MHz PowerPC processor with 6MB of RAM, the Pippin was technically a computer in console clothing. But Apple, being Apple, priced it at an eye-watering $599 when the PlayStation and Nintendo 64 were battling it out at $299. For twice the price, consumers got a vastly smaller game library and a controller that looked like someone sat on a Mac mouse.

Apple’s strategy was baffling—they didn’t manufacture the console themselves but licensed the technology to Bandai, then provided zero marketing support. Meanwhile, Sony and Nintendo were carpet-bombing the media with PlayStation and N64 ads. The result? A grand total of 42,000 units sold worldwide (18,000 in the US, 24,000 in Japan), making the Pippin about as common as a unicorn sighting.

Steve Jobs mercifully killed the Pippin upon his return to Apple in 1997, along with a slew of other failed Apple products. Two decades later, Apple would dominate mobile gaming on iOS—proving that sometimes, failure is just a very expensive learning experience.

4. RCA Studio II

The 1977 RCA Studio II answered the question nobody asked: “What if we made a gaming console that was instantly obsolete and controlled by a calculator?” Despite the “II” in its name (a marketing gimmick since no Studio I ever existed), this was RCA’s first and last gaming console—for good reason.

While Atari was revolutionizing gaming with colorful graphics and joysticks, RCA thought gamers would prefer tapping on a numeric keypad to control black-and-white blocks. The Studio II’s “graphics” resembled a calculator display, with a resolution that made Pong look like 4K Ultra HD. The system ran on an RCA COSMAC 1802 CPU—the same processor later used in NASA space probes, proving it was better suited for the vacuum of space than the competitive console market.

The built-in controllers were permanently attached to the console, forcing players to huddle around the system like cavemen around a fire. Audio came from an internal speaker embedded in the console itself, producing sounds that could best be described as “a robot having a seizure.”

The final nail in the Studio II’s coffin? It launched the same year as the Atari 2600, which offered color graphics, removable joysticks, and games that didn’t look like they were designed by accountants. The Studio II was discontinued after just a year, joining the great calculator graveyard in the sky while teaching RCA a valuable lesson: stick to making televisions.

3. JVC Wondermega

The 1992 JVC Wondermega proves that licensing someone else’s technology and making it more expensive isn’t a winning formula. This Genesis/Mega Drive with a built-in Mega-CD/Sega CD also added karaoke functionality—because nothing says “serious gaming” like drunk friends butchering 90s pop hits.

JVC licensed this technology from Sega, then had to compete against the very company they were paying royalties to. Their brilliant strategy? Charge an astronomical ¥82,800 (about $800)—nearly triple the price of buying Sega’s separate components. It’s like buying the rights to sell someone’s car, marking it up 200%, then wondering why nobody’s visiting your dealership.

The Wondermega actually had impressive specs for its time, sporting dual CPUs, built-in MIDI ports, and video capture capabilities. But no amount of technical wizardry could justify that price tag, especially when Sega was already moving toward the Saturn. JVC released a redesigned Wondermega M2 model with a lower price, but by then, consumers had already voted with their wallets.

JVC’s gaming ambitions died alongside the Wondermega, teaching the valuable lesson that just because you can combine a CD player, a game console, and a karaoke machine doesn’t mean anyone wants to pay luxury car prices for the privilege.

2. Sega Genesis 3

In 1998—a full eight years after the original Genesis launched—Majesco thought gamers were clamoring for a budget version of an obsolete console. The Genesis 3 was the gaming equivalent of releasing a VHS player during the DVD era, targeting a market that had largely moved on to PlayStation and Nintendo 64.

Majesco licensed the design from Sega, stripped out the expansion port (preventing Sega CD and 32X compatibility), removed the headphone jack, and shrunk the whole package to a size that suggested “we saved money on plastic.” The result was a console incompatible with about 20% of the Genesis library and all its accessories—a brilliant strategy if your goal is to disappoint the few customers who actually bought it.

The bizarre timing meant you could find used original Genesis systems for less than the “budget” Genesis 3’s $49.99 price tag. With no marketing support from Sega (who were busy failing with the Saturn and preparing to fail with the Dreamcast), the Genesis 3 quickly disappeared from store shelves.

The Genesis 3 stands as a testament to the age-old business wisdom: if you’re going to release outdated technology, at least make sure it works with all the games people already own. Anything less is just electronic landfill with a Sega logo slapped on it.

1. SuperGrafx

The 1989 SuperGrafx proves that adding “Super” to your product name doesn’t automatically make it successful (though Nintendo might disagree). NEC’s follow-up to their successful PC Engine/TurboGrafx-16 console promised massive improvements but delivered marginal upgrades at premium prices.

On paper, the SuperGrafx packed impressive specs for 1989: dual graphics processors, 32KB of video RAM (4× the original), and backward compatibility with PC Engine games. In reality, the performance boost was barely noticeable, and developers largely ignored the enhanced capabilities—resulting in a grand total of seven dedicated SuperGrafx games. Yes, SEVEN. You could literally play the entire console-specific library in a weekend.

Released in Japan for ¥39,800 ($299) when the original PC Engine was still selling well at a lower price, the SuperGrafx was a solution looking for a problem. NEC never even bothered releasing it internationally, quickly abandoning the hardware to focus on PC Engine CD technologies.

The SuperGrafx’s failure wasn’t due to poor quality—it was actually well-built and technically impressive. It failed because it offered too little improvement at too high a price, arriving at precisely the wrong moment in console evolution. Today, it’s a coveted collector’s item, with boxed systems selling for thousands—proving once again that in gaming, commercial failures often become valuable artifacts for those nostalgic enough to remember them.